How to Make Decisions When There’s No Best Answer

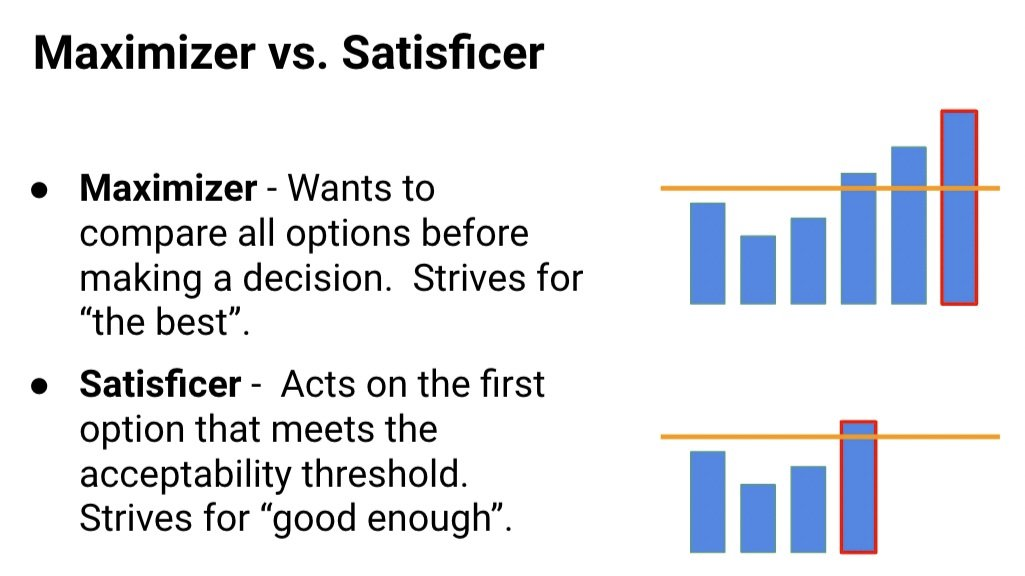

People's approaches to decision-making tend to fit into one of two categories: Maximizers and Satisficers (the word “satisfice” blends “satisfy” and “suffice”). Maximizers want to compare all options before making the “best” decision. Satisficers strive to quickly make a “good enough” decision that meets their criteria. A person can maximize when it comes to some decisions and satisfice on others.

In most aspects, I’m a maximizer. It's served me well academically and professionally. Yet I don't necessarily feel happier than my peers who are satisficers.

On the contrary, I’ve gained first-hand experience of when striving for the “best” decision is particularly counterproductive.

If you identify as a maximizer, please read on! I’m here to share insights about the common decision-making pitfalls we face and how we can adjust to make better decisions.

Not sure if you're a maximizer or satisficer? Take this 1 minute quiz.

Maximizers earn more, but are less happy

In a study published in 2006 in the journal Psychological Science, researchers followed 548 job-seeking college seniors at 11 schools from October through their graduation in June.

Across the board, they found that the maximizers landed better jobs. Their starting salaries were, on average, 20% higher than those of the satisficers, but they felt worse about their jobs.

“The maximizer is kicking himself because he can’t examine every option and at some point had to just pick something. Maximizers make good decisions and end up feeling bad about them. Satisficers make good decisions and end up feeling good.”

The researchers also found maximizers tend to be more depressed and to report a lower satisfaction with life. As a result, satisficers are happier than maximizers even though they also have high standards. The older you are, the less likely you are to be a maximizer—which helps explain why studies show people get happier as they get older.

And importantly, they found nothing to suggest that either maximizers or satisficers make bad decisions more often.

Common pitfalls of maximizers

Maximizers are terrified of “settling” for anything but the “best.”

As a result, maximizers are quite to associate satisficing with settling. However, “settling” means to pick an option that you’re consciously aware is bad, based on your criteria. On the contrary, “satisficing” means to pick an option that meets your criteria. There is no overlap between these definitions – satisficers aren’t masochists that enjoy making bad decisions for themselves. It’s crucial for maximizers to understand this difference because as we’ll discuss later, we can learn a lot from satisficers, specifically around big life decisions.

Maximizers who realize bad decisions in hindsight are often paralyzed from making future decisions.

A common self-sabotaging logical fallacy among maximizers is to blame yourself for a bad decision in hindsight, even if it seemed like a good decision at the time. Of course hindsight is 20/20. We all wish to have a crystal ball to see into the future. It’s unreasonable to ding yourself for not knowing what you didn’t know.

If you’re a maximizer with this logical fallacy, you may find yourself hesitant to make future decisions. You may worry that even if a decision seems good given the information available to you, it could turn out to be bad in hindsight once again.

This hesitance is self-sabotaging because if you procrastinate on making a decision, your choice will be made for you by circumstance, and there’s no guarantee it will be a good one. Thus, to avoid being forced into an obviously bad decision, it’s always better to proactively make at least a good-enough decision with the information available to you.

Diving deeper into the types of decisions maximizers struggle with

For sake of discussion, let’s define three simple attributes which we’ll use to organize the types of problems we face – from simple arithmetic to choosing a restaurant for lunch to deciding whether to have children.

- Consequential vs Inconsequential – Consequential decisions have lasting implications and fundamentally alter the trajectory of your life in a meaningful, possibly irreversible way.

- Well-defined vs Poorly-defined – Well-defined problems are objective and repeatable, and everyone can look at the same facts to determine which is the “best” option (e.g. Googling which entry-level sedan to buy if you care about fuel efficiency). Poorly-defined problems are subjective and unrepeatable, meaning you may not even agree with your past self about which is the “best” option (e.g. whether to have children, or where to live in your 30s).

- Many options vs Few options – This one is self-explanatory. We’re adding this attribute is to show the implications of maximizers feeling the need to consider every possible option.

The following tables shows how well I believe satisficers and maximizers are equipped to tackle each type of problem (either Great, Okay or Bad).

Maximizers are strong at Well-defined problems

| Well-defined | Poorly-defined | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conseq. | Okay (Many options) |

Great (Few options) |

Bad |

| Inconseq. | Okay (Many options) |

Great (Few options) |

Bad |

Satisficers are strong at Poorly-defined problems

| Well-defined | Poorly-defined | |

|---|---|---|

| Conseq. | Okay | Okay |

| Inconseq. | Okay | Okay |

Wow! What does this all mean? Let’s break down the insights.

Let’s start with satisficers.

Because they always focus on quickly finding the first “good enough” option, they will never do badly on a well-defined problem irregardless of how many options there are because this strategy avoids settling for a bad outcome. However, as research shows, they’ll also typically realize slightly worse outcomes than maximizers (e.g. 20% lower earnings). Thus, I gave them an “okay” rating for all four “well-defined” problem types.

Satisficers follow the same strategy for poorly-defined problems. In theory, they should get an “okay” rating for all four “poorly-defined” problem types as well. However, I feel this approach is particularly well suited for inconsequential poorly-defined problems in particular because they don’t give any more attention than these problems deserve, hence the “great” rating.

The maximizers column has a lot more complexity.

Let’s start with the “great” ratings. Maximizers thrive in well-defined problems with few options. Here, they assess all options and pick the best, regardless of how consequential it is. This is why they end up with 20% more earnings, and likely drive slightly more fuel efficient cars (assuming that’s the dominant criteria now that gas costs are sky high in late 2022).

For well-defined problems with many options, I downgraded maximizers to an “okay” rating. This is because while they’re still likely to make a better decision than satisficers, they’ll exhaust much, much more time and energy assessing all the options (if they’re even able to do so). If they’re unable to assess all the options, they’ll end up terrified they’re “settling” and be more likely to feel regret.

Now here’s the kicker: the only “bad” ratings I assigned at all were for maximizers dealing with poorly-defined problems. That’s because there’s no such thing as a “best” option for subjective, unrepeatable problems. Thus, maximizers get stuck in an endless chase. Their logical, rational methods that work so well in their academic and professional endeavors don’t get them very far.

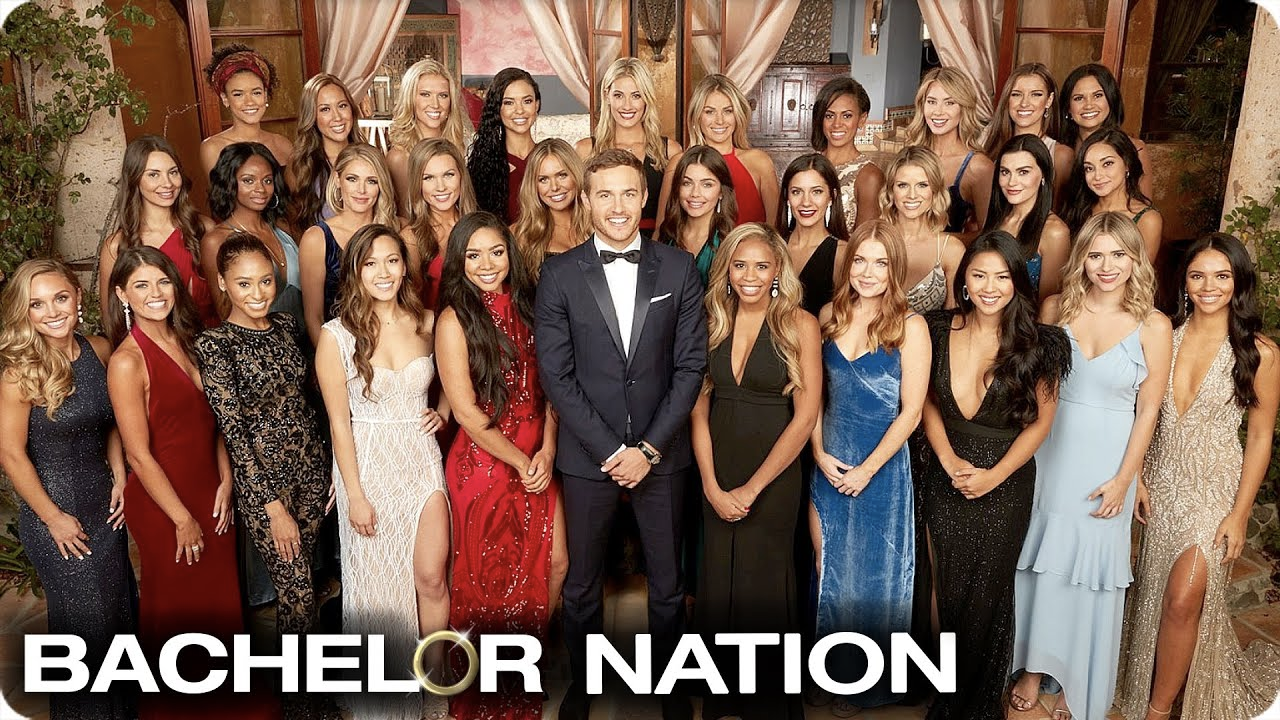

Take dating as a prime example: maximizers feel pressure to find “the one” – the best person for them on Earth. This is a consequential, subjective decision with many options – about 7 billion to be exact.

You might think that the self-critical tendencies of maximizers would lead them to make more informed, considered choices - that they would research their options more thoroughly and contemplate possible outcomes for longer before making a decision. But a study which looked at the choices people make when looking for a partner using online dating contradicts this assumption. The study looked at maximizers who would dwell upon the process of searching for a partner, exhausting their options in an effort to find 'the one'. Despite the additional effort required for this more rigorous approach to searching and arriving at a decision, the researchers found that maximizers did not necessarily benefit from it in terms of the partner that they selected (Yang and Chiou, 2010).

Researchers believe one reason satisficers are happier than maximizers is that they focus less on the options they didn’t pick and thus deal with less regret.

I believe another reason is that the biggest life decisions we face – the ones that define the fabric of our daily experience and the essence of our self-identity – are consequential, subjective problems that cannot be solved in the same way with deep analytical thinking and research. And as we can see above, satisficers fare much better with these problems than maximizers.

How Maximizers can learn from Satisficers to make better decisions

As we just saw, maximizers could immediately benefit from adopting a satisficing mindset when dealing with poorly-defined problems such as finding a partner or choosing a restaurant for lunch.

But neither satisficers or maximizers are “great” at the consequential, poorly-defined problems of life. These are the big, tough lief decisions that inspired me to create this website in the first place (e.g. what career path to pursue, who to marry, where to live in your 30s). The decisions that can irreversibly alter your life trajectory, and if done right, provide you rich meaning, purpose and fulfillment every day.

Let’s create an approach by merging the best parts of satisficing and maximizing:

From the maximizers, we’ll borrow their urgency to explore many options and deeply understand how good each one is.

From the satisficers, we’ll borrow their ability to make a “good enough” decision and their ability to focus on the pros over the cons which minimizes future regret.

Adding it all together, it should look something like this:

- First, commit to a decision deadline so you don’t get caught up never deciding and letting circumstances decide for you.

- Next, identify your criteria so you can evaluate future options. (We recommend creating criteria from your values with our Inner Compass Building protocol).

- Then, use the urgent mindset of a maximizer to broadly and deeply explore multiple options. The more data you can collect before your decision deadline, the better a decision you’ll be able to make.

- When your decision deadline arrives, exclude all options that are bad decisions. Now you’ll be able to set aside your fear of settling for a bad decision.

- Use the mindset of a satisficer to confidently select a decision that is “good enough.” Focus on the pros, not the cons. Remind yourself that the concept of a “best” decision is counterproductive for subjective decisions like these.

- After making your decision, use the mindset of a satisficer to minimize “buyer’s remorse.” Appreciate that you made a great decision within a reasonable amount of time while expending a reasonable amount of energy.

This isn’t the only way to tackle the big, tough life decisions that brought you here in the first place. But it is easy to follow and helps maximizers (and satisficers) find greater fulfillment and satisfaction. And with enough practice, us maximizers may find our way to equal happiness with satsificers.

Seductive but fake solutions

Converting poorly-defined problems into proxy well-defined problems by setting some assumptions and stripping some nuance, then solving the proxy with a maximizing approach.

There are countless self-help, motivational gurus who preach this approach. And it makes sense – it is the easy way out, and if it worked, it’d be easier than learning a new decision-making approach. People are drawn to types of problems they feel confident solving.

But this is a false sense of security. Doing so cuts out the key nuance that makes poorly-defined problems so difficult yet important. Doing so makes living feel mechanical instead of organic and inspirational. And doing so makes you less likely to find happiness, conviction, satisfaction or purpose because the proxy goals you decide to pursue may wilt or lose their charm as you progress through life, and slowly but surely you'll find yourself more and more out of touch with your desires.

Outsourcing decision making to someone else, which is especially seductive if they are great at solving their own poorly-defined problems.

This is appealing because you feel you can trust someone else’s wisdom. But unless their values and live experiences magically match yours, their decisions will align your life trajectory to their beliefs, values and prioritize rather than your own. Click here to read more about how life advice can be a trojan horse.

Enjoy our blog?

Forward to a friend and let them know they can subscribe (hint: it's here).

Have requests or feedback? Hit reply to suggest topics, send feedback or say hello.

Feeling mediocre or directionless? Explore our "Inner Compass Building" protocol that helps ambitious people build internal conviction, make urgent decisions, and minimize regret.